June 2000 (Part 3)

SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

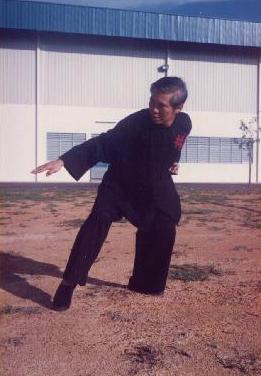

My Wing Chun master, Sifu Choe Hoong Choy

Question 1

First I'd like to express my great thanks for your book: The Complete Book of Zen. That book happened to find me in a time when I was low and I count it as one of the most influential readings of my life. I even found out that I was practicing Zen before I knew it by that name.

— Daniel, UK

Answer

It is actually common that many people are practising Zen without their knowing. But you are one of the very few who have the perception to realize it. Congratulations.

That is why when students asked their master to teach them Zen, the master might reply like “Have you eaten your meals?” or “Go and wash your dishes”.

How these questions and answers are interpreted, depends on numerous factors, such as the students level of development and the teacher's intention. One interpretation is that Zen is in our everyday life, you need not go into a forest or a temple to practise Zen. Another interpretation is that Zen is practical — you do Zen, not study Zen.

These questions and answers also reveal three fundamental qualities of Zen, namely simplicity, directness and effectiveness. The master's teaching is simple (but not simplistic); he does not give a long discourse on what Zen is. His teaching is direct; he does not hide his teaching in arcane language, as is frequent in Taoist teaching. It is effective; as soon as his students eat their meals or wash their dishes, they practise Zen.

Similarly, in my chi kung courses I tell my students to close their eyes, relax and smile from their hearts. My teaching is also simple, direct and effective. I do not give a long discourse on how to relax, I do not use high flown language like “let the lids of your soul's window kiss their counterparts like petals falling softly onto tranquil water”, my students have the effect immediately. My students, too, practise Zen, often without their knowing.

Of course the uninitiated will be puzzled. They will wonder how on earth is eating meals or washing dishes practising Zen. They also wonder how to relax and smile form their hearts. They will not be able to achieve any beneficial effect because those instructions are not meant for them.

The Zen master's instructions are meant for students who have spent many years practising in his temple; my instructions are meant for students who attend my intensive chi kung course. In both cases, the students have been adequately prepared. Others who learn the same instructions from a book or a webpage cannot have the same result.

But you will understand. If you were low, for example, you would know how to practise Zen to lift up your spirit — not by analysing your emotions or studying the works of Zen masters, but simply, directly and effectively by going out to have some sunshine, or to eat a meal or wash some dishes.

Question 2

I was overjoyed when searching the Net for some additional reading on Zen. I found that you not only had an email address, but a masterfully designed webpage (shaolin-wahnam.org) as well. I'm also intrigued by your relating Shaolin Kungfu and Zen and I see that I should begin to practice it.

Answer

Your response shows the benefit of Zen on you — you “practice” Zen, not just “study” it.

Shaolin Kungfu, Chi Kung and Zen are integrated. When you practise genuine Shaolin Kungfu, you are at the same time practising chi kung and Zen. When you practise Shaolin Chi Kung, you are also practising Zen and “kungfu”, and when you practise Zen, you are also practising “kungfu” and chi kung.

The following explanation is not accurate, but it gives people who are used to rigid scientific thinking, some ideal of the above integration. Kungfu involves training the physical body, chi kung the training of energy, and Zen the training of mind. Shaolin philosophy considers a person holistically. Any development, therefore, must involve the physical body, energy and mind.

An application from “Fa Khuen” (Flower Set) of Choe Family Wing Cun Kungfu. Sifu Wong strikes Peter's left temple. As soon as Peter blocks the strike, Sifu Wong “threads” away the defence and strikes at the same spot again.

Question 3

My last two questions are far easier and I must apologize in advance for bothering you with such mundane queries. Both are questions from my Buddhism class at the University of Mississippi and are questions regarding the Chinese writing in characters of some concepts and people.

First, if you had to write Zen as a character, what would the calligraphy look like? And my teacher said that she would not accept a simple circle as was my initial answer drawn from your book.

Answer

I am sorry I do not know how to write Chinese characters in my e-mail. Hence I cannot show you in this e-mail how the Chinese character for Zen look like. Its Romanized Chinese spelling is “chan”.

The simple circle on the cover of my Zen book was not provided by me; it was provided by my publisher. Although I also like this simple circle, I would prefer the Chinese character “chan”.

Nevertheless, if you ask me how I would write Zen as a character, in the sense that I would create a character or picture to represent Zen, I would answer, “Have you checked your e-mails?”

If a Zen reader, as distinct from a Zen practitioner — that is, one who reads about Zen, and not one who actually practises Zen — asked me the same question, I would answer as follows. Why do you bother to create a new character or picture to represent Zen?

The word “Zen” or “chan” or its writing in Japanese, Chinese or Sanskrit is good enough. Instead of worrying about what the character should look like, an attitude which is in fact most unZen-like, you will get more Zen benefits by being aware of the present moment.Question 4

Second, there is a Zen story of a monk named Ensnared-Light and I was wondering how his name would be written in character.

Answer

I do not know about Ensnared-Light, nor his name in Chinese characters.

Actually it does not matter how the Chinese characters look like, or whether his name is Ensnared-Light. In typical Zen spirit, you can call him Purple Snow if you like.

Peter turns from his Bow-Arrow Stance sideways to avoid Sifu Wong's attack, and simultaneously executes a punch to Sifu Wong's right ribs. Sifu Wong “opens” Peter's hands, thus frustrating his attack, and strikes a vertical fist into Peter's left ribs.

Question 5

I have heard many different stories on the history of Wing Chun Gung Fu. Some have said that the Yim Wing Chun story was made up to hide the real story behind Wing Chun.

— Philip, South Africa

Answer

The history accepted by most Wing Chun practitioners as well as by most practitioners of other kungfu styles is that Wing Chun Kungfu was initiated by Yim Wing Chun. She learned Shaolin Kungfu from the female grandmaster, Ng Mui (Wu Mei in Mandarin pronunciation).

Ng Mui's favourite kungfu set was the Shaolin Flower Set, and it was most likely that this was what she taught Yim Wing Chun. Later Yim Wing Chun, known to be pretty and gentle, married a rich merchant named Leong Pok Khow who loved her very much. She continued to practise her Shaolin Kungfu diligently, but modified it to suit her needs.

Yim Wing Chun taught her husband her kungfu, more as a hobby than as an art for fighting. Leong Pok Khow had two disciples, namely Wong Wah Poh and Leong Yi Tai. When asked what kind of kungfu it was, Leong Pok Khow would reply, “Oh, it's Wing Chun's kungfu.”

I am not aware of other stories contradicting this history of Wing Chun Kungfu, which I believe is true. My conclusion is based on the following.

There are many versions of Wing Chun Kungfu today but probably the most famous is the one from the great master Yip Man. Yip Man, who learned Wing Chun Kungfu from Chan Wah Soon, would not have seen Yim Wing Chun, but he should have seen his teacher's teacher, Leong Chan, who was nicknamed Wing Chun Kungfu King during his times. Thus, although Yip Man could not be sure whether Yim Wing Chun really existed, he could be sure that Leong Chan did exist.

In his turn, Leong Chan might not have met Yim Wing Chun but he certainly was sure that Wong Wah Poh, from whom he learned his kungfu, existed. Wong Wah Poh should have seen Yim Wing Chun in person, as she was his teacher's wife. And all these masters, who could confirm without doubt that their own teacher was real, traced in turn to Yim Wing Chun as the one who initiated Wing Chun Kungfu.

The above reason by itself cannot prove that the Yim Wing Chun story is true, but it does give weight to its verity. It is also supported by my own Wing Chun lineage. At the time when I learned Wing Chun Kungfu from my teacher, Choe Hoong Choy, Wing Chun Kungfu was relatively unknown, and taught in private only to exclusive students. (Wing Chun became well known only after Yip Man's celebrated student, Bruce Lee, became famous.)

My Wing Chun lineage is as follows. Choe Hoong Choy — Choe Onn — Choe Chun — Choe Tuck Seng — Choe Shun — Yik Kam — Leong Yi Tai — Leong Pok Khow — Yim Wing Chun. Each master could confirm the actual existence of the earlier one, and all of them mentioned Yim Wing Chun as the start of the lineage. If someone today claims to be descended from the Wing Chun lineage, although in reality he is not, it is understandable because Wing Chun Kungfu is now famous. But at the time when Wing Chun Kungfu was actually unknown, I could not think of a better reason to claim this lineage except that it was true.

As an academic issue, what I regard to be more interesting and rewarding is to find out which of the many versions of Wing Chun Kungfu today is closest to the original Wing Chun Kungfu taught by Yim Wing Chun and the early masters. The numerous versions include Yip Man Wing Chun, Choe Family Wing Chun, Yen Kat San Wing Chun, Go Law Wing Chun, and Red Boat Wing Chun. Robert Chu, Rene Ritchie and Y.Wu have written an excellent book on these various versions in “Complete Wing Chun”. By far the most popular version is Yip Man Wing Chun, so widely practised that many people, including some students of other Wing Chun versions, regard Yip Man Wing Chun as the standard version.

What I find intriguing is that the version of Wing Chun I learned, Choe Family Wing Chun, is very different from Yip Man Wing Chun in many aspects. Choe Family Wing Chun is also known as Pan Choong Wing Chun, or Opera House Wing Chun (but different from Red Boat Wing Chun) because it originated from the Opera House of the Red Boat. A Red Boat was a huge boat housing opera actors. It is a comparatively little known version of Wing Chun Kungfu, and its practitioners are generally not keen to popularize it.

The most obvious difference is that while Yip Man Wing Chun uses mainly the Goat Stance and the Four-Six Stance, Choe Family Wing Chun uses mainly the Horse-riding Stance, the Bow-Arrow Stance and the False-Leg Stance although the Goat Stance and the Four-Six Stance are also part of its repertoire.

The kungfu sets of Yip Man Wing Chun encompass the three unarmed sets of Siu Nim Tao (Small Intentions), Cham Kiu (Sinking Bridge) and Piu Chee (Shooting Fingers), and the two weapon sets of Luk Tim Poon Khuan (Six-and-a-Half-Point Staff) and Pat Cham Tou (Eight Chop Knives).

Choe Family Wing Chun has a great number of both unarmed and weapon sets, including Siu Lin Tao (Small Beginning), Fa Kuen (Flower Set), Shui Ta (Miscellaneous Combat), Chui Pat Seen (Eight Drunken Immortals), Fu Hok Seong Ying (Tiger-Crane Double Forms), Cheen Cheong (Arrow Palms), Choy-Li-Fatt, Luk Tim Poon Khuan (Six-and-a-Half-Point Staff), Yen Tze Tou (Human-Character Knives), Tan Tou (Single Knife), Seong Tou (Double Knives), Yun Pin (Soft Whip), Wang Tao Thang (Bench), Yin Cheong (Spear), Kwan Tou (Big Knife) and Tai Phar (Big Trident).

Cham Kiu (Sinking Bridge) and Piu Chee (Shooting Fingers) are not practised as separate sets, but are incorporated into Siu Lin Tao (Small Beginnings), which is therefore much longer than the Siu Nim Tao (Small Intentions) of Yip Man Wing Chun. In Choe Family Wing Chun, Siu Lin Tao is the “seed” of Wing Chun Kungfu; all students must practise this set.

Luk Tim Poon Khuan is considered the most advanced set. Why has it six and a half techniques, and not seven? Sifu Choe Hoong Choy, the late patriarch of Choe Family Wing Chun, told me that this half technique was taught and explained only to inner-chamber disciples. I had the rare privilege to learn it, and its application is indeed marvellous.

Reviewing the various versions of Wing Chun Kungfu, I have found the following interesting points.

- All versions have the three unarmed sets of Siu Nim Tao or Siu Lin Tao, Cham Kiu and Phiu Chee, and the two weapon sets of the Six-and-a-Half-Point Staff and the Butterfly Knives called variously as Pat Cham Tou, Yen Tze Tou or Yi Tze Tou. As mentioned above, in Choe Family Wing Chun, Cham Kiu and Phiu Chee are incorporated into Siu Lin Tao.

- The most popular version, Yip Man Wing Chun, has the least number of sets — the five fundamental sets mentioned above. Probably the least known version, Choe Family Wing Chun, has probably the most number of sets — more than twenty. The other versions range between these two versions.

- Except in the weapon sets, Yip Man Wing Chun uses mainly the Goat Stance and the Four- Six Stance. All the other versions frequently use the Horse-Riding Stance, the Bow-Arrow Stance and the False-Leg Stance, besides the Goat Stance and the Four-Six Stance.

Personally, my conclusion is as follows:

- The early masters — including Yim Wing Chun, the first patriarch, and Leong Chan, the Wing Chun King — practised many different unarmed and weapon sets, and used various stances, including the Bow-Arrow Stance and the False-Leg Stance, in combat. Leong Chan, for example, was reputed to use the soft whip to fight himself out of an ambush.

-

From the various kungfu sets she knew, Yim Wing Chun chose those

techniques she found most useful for her particular needs, and for convenience of training she linked these techniques into one set which she would practise at the start of her training session. After her marriage to a wealthy merchant and used to wearing long skirts, she found wide stances like the Horse-Riding Stances and the Bow-Arrow Stance (which she could easily performed while wearing trousers before her marriage) not suitable and therefore preferred the shorter Goat Stance and Four-Six Stance.

-

This set has come to us today as Siu Lin Tao, or in three sets as Siu Nim Tao, Cham Kiu and Phiu Chee. Sifu Choe Hoong Choy told me that Siu Lin Tao, which word-for-word means “Small-Practice-Beginning” was so named because Yim Wing Chun always started her training with this set.

-

Hence, leaving aside the weapon sets for the time being, depending on one's perspective or loyalty, he (or she) may consider Yip Man Wing Chun as the “purest” version because the three sets practised in this version constitute the very techniques that Yim Wing Chun “invented”; or he may consider this version as the farthest from the original because it has left out much of what early Wing Chun masters practised.

-

On the other hand, Choe Family Wing Chun may be considered as the closest to the original because it encompasses most of what the early masters practised and employed in their combat. For example before her marriage to Leong Pok Khow, an unwelcome suitor who was a local bully tried to force Yim Wing Chun into marriage. She would have used techniques from Siu Lin Tao to defeat this bully in a one-to-one combat, but when she had to fight his numerous followers, it would be unwise to use those techniques, which are not so suitable for fighting a crowd. She would have selected techniques from Fa Kuen (Flower Set) or Fu-Hok (Tiger-Crane) which would give her better technical and tactical advantages.

-

Or, Choe Family Wing Chun may be considered as the farthest from the original because those techniques “invented“ by Yim Wing Chun and therefore regarded as Wing Chun Kungfu proper, forms only one set, Siu Lin Tao, out of more than twenty sets of its repertoire. The purists could argue that the other sets are Ng Mui Kungfu, Hoong Ka Kungfu, Choy-Li-Fatt Kungfu or kungfu of various Shaolin styles, but not Wing Chun Kungfu.

- The Six-and-a-Half-Point Staff and the Butterfly Knives set were not invented by Yim Wing Chun. The staff set was taught by Shaolin Grandmaster Chee Seen, the abbot of the southern Shaolin Monastery, to Leong Yi Tai on board a Red Boat. The Butterfly Knives set was exchanged by a Choy-Li-Fatt master with Leong Yi Tai for the staff set.

“Precious Duck Through Lotus” also known as “Eighth-Ten Arrow Punch”

Question 6

Do you have any information on how Wing Chun was developed in the Shaolin Temple?

Answer

Neither Yim Wing Chun nor her teacher the Venerable Ng Mui stayed at the Shaolin Monastery, which did not house any females. Ng Mui had a small temple near the monastery, but she travelled often, especially in the province of Yunnan. Hence, Wing Chun Kungfu did not develop in the Shaolin Monastery, nor was it taught there at any time.

There are, nevertheless, two other Shaolin styles also known as Wing Chun Kungfu. One of these was actually Shaolin Kungfu practised inside the southern Shaolin Monastery itself, in a hall named Wing Chun which means “Ever Spring”. Over the years there might be different kungfu sets practised in the Wing Chun Hall, but the dominant set was Fa Kuen or Flower Set.

In fact it was this Flower Set that Ng Mui taught Yim Wing Chun. To differentiate this style of Shaolin Kungfu from other styles taught elsewhere in the same monastery, this style was sometimes called Wing Chun Kungfu, different from, for example, Lohan Kungfu taught in the Hall of Lohans.

Another style of Wing Chun Kungfu is the one named after the style of Shaolin Kungfu widely practised in the Wing Chun or Ever Spring District of Fujian Province. This was White Crane Kungfu. Hence the full name of this style, which is quite different from the Wing Chun Kungfu of Yim Wing Chun as well as different from Shaolin Wing Chun Flower Kungfu, is Shaolin Wing Chun White Crane Kungfu.

To make matter more complicated, or interesting, there was another female kungfu master named Fong Wing Chun who lived in Wing Chun District. Her “Wing Chun” in Chinese means “Ever Spring”, the same as the Wing Chun Hall of the southern Shaolin Monastery, and the same as the district she lived in, but different from “Wing Chun” of Yim Wing Chun which means “Poetic Spring”. Fong Wing Chun also practised Shaolin Wing Chun White Crane Kungfu, whereas Yim Wing Chun practised Shaolin Wing Chun Flower Kungfu.

The many stories about Wing Chun Kungfu relate to these various different forms of Wing Chun Kungfu. Those who mistakenly think that there is only one form of Wing Chun Kungfu may also mistakenly think that these other stories contradict the Yim Wing Chun story.

Question 7

I understand that Kungfu, a multifaceted system, is a system of combat, and hence dominant and superior combat power is its highest priority.

— Ardeshir, USA

Answer

It is a matter of perspective. I would view kungfu in this way. Kungfu as a mutifacted martial art, has three levels of attainment. The lowest level is combat efficiency. This is also the most fundamental level, without which (i.e. without combat efficiency) it ceases to be kungfu and degenerates into a demonstrative form.

The intermediate level is internal force training. With this level of attainment, the kungfu exponent has radiant health and vitality for his daily work and play. Although I consider this level higher than that of combat efficiency, it is not fundamental (i.e. essential). Hence, some styles of kungfu may be only physical and external, without any internal force training; they may not contribute to health and vitality but if they can be combat efficient, they are kungfu.

The highest level is spiritual cultivation. With this attainment, the exponent is joyful and peaceful with himself and with the whole cosmos. At the apex, which happens to only rare masters, the exponent attains the highest spiritual fulfilment, called variously as return to God, unity with the Great Void, or enlightenment.

These three levels of attainment in kungfu are not necessarily progressive. In other words, it is not necessary for an exponent to be proficient at one level before progressing to the next. All the three levels are integrated and trained simultaneously.

False Leg Hand Sweep

Question 8

So, even though they clearly don't and aren't designed to take away from their own effectiveness, why are kungfu techniques artistic in form or appearance? Why is there a preference for artistry in kungfu techniques?

Answer

I reckon that by asking why kungfu techniques are artistic you are asking why they are beautiful to watch. There are three factors, amongst others, contributing to their beauty, namely power, balance and elegance.

Many people consider the following patterns beautiful — “Precious Duck Swims through Lotus”, “Naughty Monkey Kicks at Tree” and “False Leg Hand Sweep”.The first pattern, “Precious Duck Swims Through Lotus”, which is also known as “Eighth-Ten Horse-Riding Arrow Punch” is beautiful because of the power of the punch. The second pattern, “Naughty Monkey Kicks at Tree”, is beautiful because of good balance. The third pattern, “False Leg Hand Sweep” is beautiful because of its elegance.

The beauty of their form or appearance does not take away from their combat effectiveness. In fact it is the reverse. When performing these patterns the exponent is powerful, has good balance and is elegant, not because he wants to make them look beautiful but because these qualities make him a better combatant.

Hence, in kungfu there is no conscious preference for artistry, in the sense of being beautiful to watch. The fact that kungfu performance is beautiful to watch is not done on purpose; it is an incidental bonus.

Question 9

Does it serve a function or did Kungfu creators just like it that way?

Answer

The beauty in kungfu serves its combat function. These beautiful patterns were not consciously created, but were evolved through centuries of actual fighting.

In other words, the kungfu patterns are the ways they are now, not because someone thought out their forms, but because when kungfu exponents fought, they found that by reacting in certain ways in certain combat situations, they could secure certain combative advantages, and through time these ways of actual fighting crystallized into the present kungfu forms and movements.You would have more information about the functional beauty of kungfu if you refer to my webpages on Is Kungfu too Flowery for Combat? and The Amazing Techniques of Shaolin Kungfu.

Question 10

By the way, I like kungfu and unlike the people who wish to appear as though they are objectively criticizing kungfu by questioning its “flowery”, “fancy”, or “artsy” aspects but in reality are attacking it in an effort to insult and defame, I am just curious to know what the preference for artistry in Kungfu is about?

Answer

If you like kungfu because it is beautiful to watch, then you have missed its essence. Real kungfu exponents never intend their art to please spectators. If you suggest that they do so, you are actually insulting and defaming them — you suggest that their art is not real kungfu, but “flowery fists and embroidery kicks”.

If you are looking for something beautiful to watch, you should see modern wushu. It is not only artistic, it is magnificent.

Contrary to what you thought, many among those who criticize kungfu for being flowery, fancy or artsy, do so not because they want to insult or defame it, but because being unable to apply kungfu for combat they have become frustrated, and they attempt to simplify it into something like karate or taekwondo for combat. Bruce Lee was an outstanding example. Others include many founders of various kungfu-dos.

The big irony is that in their attempt to make kungfu more combat efficient, they have succeeded in making it shamefully inferior, sometimes to an extent that it has lost its kungfu characteristics. Kungfu in its traditional form is exceedingly combat effective. Irrespective of whether we debate its combat effectiveness from the viewpoint of techniques, tactics, strategies, force, speed, energy management and mind control, kungfu is far, far superior to any other martial art known today.