August 2000 (Part 2)

SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

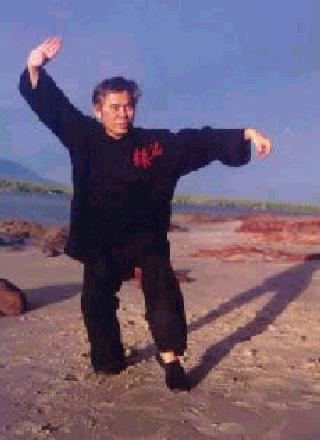

Sifu Wong demonstrating a pattern from Chaquan, the style of kungfu widely practiced by Muslims in China

Question 1

What are the contributions of Muslims in the development or spread of chi gung and martial arts?

— Samuel, USA

Answer

Arts of energy management and of combat are, of course, not confined to the Chinese only. Peoples of different cultures have practised and spread these arts since ancient times. Those who follow the Chinese tradition call these arts chi kung and kungfu (or qigong and gongfu in Romanized Chinese), and those following other traditions call them by other names.

Muslims in various parts of the world have developed arts of energy management and of combat to very high levels. Many practices in Sufism, which is spiritual cultivation in Islamic tradition, are similar to chi kung practices. As in chi kung, Sufi practitioners pay much importance to the training of energy and spirit, called “qi” and “shen” in Chinese, but “nafas” and “roh” in Muslim terms.

When one can free himself from cultural and religious connotations, he will find that the philosophy of Sufism and of chi kung are similar. A Sufi practitioner believes that his own breath, or nafas, is a gift of God, and his ultimate goal in life is to be united with God. Hence, he practises appropriate breathing exercises so that the breath of God flows harmoniously through him, cleansing him of his weakness and sin, which are manifested as illness and pain.

And he practises meditation so that ultimately his personal spirit will return to the universal Spirit of God. In chi kung terms, this returning to God is expressed as “cultivating spirit to return to the Great Void”, which is “lian shen huan shi” in Chinese. Interestingly the breathing and meditation methods in Sufism and in chi kung are quite similar.

Some people, including some Muslims, may think that meditation is unIslamic, and therefore taboo. This is a serious mis-conception. Indeed, Prophet Mohammed himself clearly states that a day of meditation is better than sixty years of worship. As in any religion, there is often a huge conceptual gap between the highest teaching and the common followers. In Buddhism, for example, although the Buddha clearly states that meditation is the essential path to the highest spiritual attainment, most common Buddhists do not have any idea of meditation.

The martial arts of the Muslims were effective and sophisticated. At many points in world history, the Muslims, such as the Arabs, the Persians and the Turks, were formidable warriors. Modern Muslim martial arts are very advanced and are complete by themselves, i.e. they do not need to borrow from outside arts for their force training or combat application — for example, they do not need to borrow from chi kung for internal force training, Western aerobics for stretching, judo and kickboxing for throws and kicks.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, for instance, some masters of Silat — which is the Malay word for martial art and is usually practised by Muslims although non-Muslims may also practise it — have incredible internal force. Not only they can take strikes by iron bars and axes on their body without harm, they can inflict injury on their opponents from a distance without immediate physical contact.

It is reasonable if sceptics ask, “If they are really so advanced, why don't they take part in international full contact fighting competitions and win titles?” The answer is that they hold different values. They are not interested in fighting or titles. At their level, their main concern is spiritual cultivation. Not only they will not be bothered whether you believe in such abilities, generally they are reluctant to let others know of their abilities.

Muslims form a substantial portion of the population in China, and they have contributed an important part in the development of chi kung and kungfu. But because the Chinese generally do not relate one's achievements to one's religion, the contributions of these Chinese Muslim masters did not carry the label “Muslim” with them.

In fact, in China the Muslim places of worship are not called mosques, as in many other countries, but are called temples. Most people cannot tell the difference between a Muslim temple, and a temple of other religions, such as Confucian, Taoist or Buddhist, because they all look the same from outside. The initiated will know: Muslim temples are called Qing Zhen Si, which means Temples of Purity and Truth.

It is, however, well known that Chaquan, which means Cha Kungfu, is widely practised by Muslims. Chaquan is a style of Northern Shaolin Kungfu, and is as beautiful to watch as it is combat effective. It is named after a great Muslim kungfu master called Cha Mi Er, which is the Chinese pronunciation for the Muslim name “Jamil”. Another great Muslim master was Cheng Ho (or “Zhen He” in Romanized Chinese). He was the Admiral of the Ming Dynasty who led a gigantic fleet from China to as far as east Africa.

Editorial Note : Sameul kindly replied as follows:

I am speechless when I see this very informative message which is proof of your courtesy and knowledge. I thank you for your excellent message and hope to hear more about the subject.

Note about chi kung/meditation being taboo:

In the Quran (sacred text of the Muslims) there are a lot of verses that imply or directly say of self-purification, such as:

-

Verily never will Allah change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves.

S.13 A.11

Question 2

Thank you very much for your answers. Concerning the grappling and ground fighting, I have heard a story told by my Sigung Lam Cho, about his uncle and teacher Lam Sai Weng.

A jiu-jiutsu champion, who was a high ranked navy admiral from Japan, started to learn in Lam Sai Weng's school, but he did not reveal the fact he was a jiu-jitsu practitioner and champion. After one month or so he said, “I do not believe this stuff could be useful in fighting. You are just practising deep stance, breathing, slow movements. It is useless.” So he challenged “Porky Weng”.

He tried to grab Lam Sai Weng's leg and take him to the ground, but Lam Sai Weng's immovable stance was very stable. Lam took one step forward and drove a devastating tiger-claw to his opponent's head and knocked him down. After the Japanese woke up he apologized and invited Lam Sai Weng to his ship and fired a salvo to celebrate Lam Sai Weng and his skill.

— Pavel, Czech Republic

Answer

Lam Sai Weng was a great southern Shaolin master. A jiujitsu champion would be no match against him. It was compassionate of Master Lam not to hurt the jiujitsu champion.

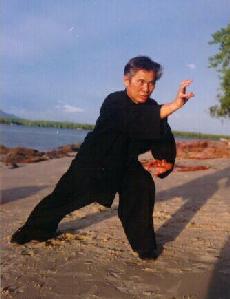

"Hungry Tiger Catches Goat" from the Shaolin Tiger-Crane Set

Question 3

In our school we try to practice traditional gungfu. We do not practice a lot of sets. Our basic curriculum consists of 4 empty-hand sets, namely Taming the Tiger, Tiger and Crane, 5 Animals 5 Elements and Iron Thread.

We do a lot of single exercises (practising selected techniques over and over), a lot of 2-man sets (Taming the Tiger 2-man set, Tiger and Crane 2-man set), a lot of specific techniques and a lot of additional exercises to develop inner power (stance training, forearm conditioning - not the external method, Grandmaster prefers to build the power from inside out, finger strengthening exercises etc.).

Answer

Taming the Tiger, Tiger and Crane, and Iron Thread (or Iron Wire) are the three classical sets of Hoong Ka Kungfu. These three sets, if practised correctly and without addition of any kungfu or other exercises, are enough for the exponents to be extremely combat efficient as well as healthy, fit and full of vitality.

Yours is a typical way of traditional kungfu training. If more of other schools follow your school's example, the standard of kungfu will be greatly enhanced, and kungfu students won't be a laughing stock among other martial artists.

The question whether kungfu is realistic for fighting will not arise. It is worthwhile to point out for others who may not realize it, that the emphasis of your school is combat efficiency and force training, in clear contrast to many other schools where the emphasis is set demonstration to please spectators.

Question 4

I am interested in knowing about the Eight Immortals style of Kung Fu. I saw a page that traced its origins back to the Wudang Temple. From my understanding, the Wudang Temple is famous for three styles: Baguazhang, Xingyiquan, Taijiquan, and I've seen Liuhebafaquan included.

— Yu, USA

Answer

I am not sure whether the “Drunken Eight Immortals“ set originated from the Wudang Temple, but I don't think it did.

“Drunken Eight Immortals” is not a style by itself, using the generic term "style" here to mean a particular style or school of kungfu like Eagle Claw Kungfu, Choy-Li-Fatt Kungfu and Taijiquan. Rather, “Drunken Eight Immortals” is a kungfu set, and it is found, in different versions, in some kungfu styles like in Chow Ka Kungfu and in Choe Family Wing Choon.

Wudang Taijiquan, from which various styles of Taijiquan later developed, originated from the Wudang Temple in the 13th century. But Baguaquan and Xingyiquan — the other two of the three famous internal kungfu styles — are actually not related to the Wudang Temple, although many people conveniently grouped these three styles of internal kungfu as Wudang Kungfu. This is probably the biggest mistake in kungfu classification, but it has been so established that many people wrongly accepted it as valid.

Baguaquan, the latest of the three internal arts, was founded by Dong Hai Chuan in the 19th century on Jiu Hua Mountain, and not on Wudang Mountain. But his teacher could be a Taoist master from the Wudang Temple.

Xingyiquan was the earliest of the three internal arts. It was developed from Shaolin Kungfu by the great Song Dynasty general Yue Fei in the 12th century. It was initially called Liuhebafa, which means “six harmonies and eight methods”. In the 17th century Ji Long Feng consolidated it, and it became popularly known as Xingyiquan.

Question 5

I read elsewhere on your page that “drunken kungfu” refers to a specific set within a style, such as drunken crane or drunken monkey.

If memory serves me correctly, it is the style of kungfu demonstrated in Jackie Chan's movie, the Drunken Master. Eight Immortals does indicate Taoist origin, but might it be related to the other Shaolin drunken styles? Any insight is greatly appreciated.

Answer

Your questions indicate an interesting contrast between Eastern and Western way of thinking. Eastern thinking is intuitive and holistic, whereas Western thinking is intellectual and analytical.

Your questions would not arise in Eastern thinking because it does not bother whether a term like “Drunken Kungfu” refers to a set or a style, or why could something that was Taoist in origin relate to styles of Shaolin which are Buddhist in nature. To an Eastern mind, asking such questions is like asking whether “New York” refers to a city or a state, or why the English name “John” is used by a Chinese man.

Will there be confusion if someone says “I practise Drunken Kungfu or Wing Choon Kungfu”? No, there will be no confusion because nobody will bother whether “Drunken Kungfu” or “Wing Choon Kungfu” refers to a set or a style. The practitioners are not concerned with intellectualization or analysis; their concern is how well their kungfu training make them healthy and combat efficient.

In fact there is no direct equivalent in Chinese for the term “style” as we use it here. If you wish to ask someone what style of kungfu he practises, i.e. whether it is Baguazhang, Taijiquan or Shaolin Kungfu, you would have to ask “What kungfu do you practise?”, to which he may rightly answer like, “I do a lot of force training” or “I usually perform kungfu sets”.

Then, how would you ask in Chinese whether his style is Baguazhang, Taijiquan or Shaolin Kungfu? You would ask what “pai” (branch) or “ka” (family) his kungfu is, to which he may reply Southern Branch or Hoong Ka. Isn't this confusing?

No. Confusion arises only when you attempt to impose rigid classification when it does not exist. Then how would you know whether his style is Baguazhang, Taijiquan or Shaolin Kungfu? Simple; you ask him directly, “Do you practise Baguazhang, Taijiquan or Shaolin Kungfu?”

Yes, the kind of kungfu demonstrated in Jackie Chan's movie, “Drunken Master” is Drunken Kungfu. The version of Drunken Kungfu shown in this movie is “Drunken Eight Immortals”, which is a kungfu set. The style or school of kungfu in which this “Drunken Eight Immortals” is found is Southern Shaolin or Hoong Ka. The Drunken Master, Su Hat Yi or Beggar Su, was a Hoong Ka master and one of the “Ten Tigers of Guangdong”.

Now, if somebody asks, “I practise Hoong Ka, but why is this Drunken Eight Immortals set not found in my school, or in any of the Hoong Ka schools I have seen?”, he is demonstrating rigid Western thinking. If someone says, “Drunken Eight Immortals is Taoist, how is it found in Shaolin Kungfu, which is Buddhist?”, again he is compartmentalizing.

It is true that the Drunken Eight Immortals is not usually found in the repertoire of Hoong Ka Kungfu, but that did not limit Su Hat Yi, a Hoong Ka master, from learning and then becoming expert in this type of kungfu. It is true that the Drunken Eight Immortals is Taoist in origin, but that does not mean Buddhist disciples of Shaolin Kungfu cannot be proficient in it.

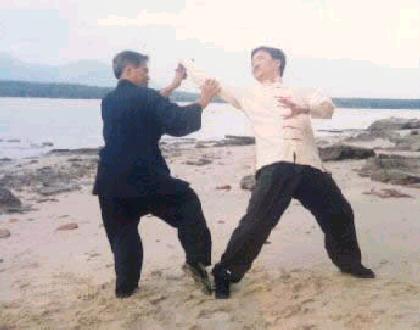

Shaolin qin-na. After some preliminary movements Sifu Wong grasps (qin) Goh Kok Hin's right wrist and grips (na) Goh's right elbow in a pattern called "Intelligent Monkey Fells a Tree". Notice that Sifu Wong positions himself so that it is difficult for the opponent to counter-attack.

Question 6

Sifu, what are heng and ha sounds?

Some people said that these two sounds are very important and the sounds can be implemented while we are taking the breath in and out.

Are these sounds similar to ordinary sounds as we say heng and ha or are there some secrets in them?

— Stanley, Indonesia

Answer

Heng and ha are two sounds made while breathing in and out in some styles of chi kung, like Wantankung, or External Elixir Chi Kung.They may be important in some styles of chi kung, but are not needed in most other styles. Indeed most of the popularly practised chi kung today, like Eighteen Lohan Hands, Five-Animal Play, Soaring Crane Chi Kung, and Chanmigong, do not need these two sounds.

Heng and ha are not made like when one says "heng" and "ha" ordinarily. They are made by letting the in-breath vibrating the lungs, and the out-breath coming from the abdomen. The sounds are long and sonorous.

Actors in Cantonese opera worship the "Two Heng Ha Generals" as guardian gods. According to Cantonese opera legends, two young boys helped opera actors to develop sonorous voices in their singing. When the actors wanted to thank the boys, they ran away. The actors chased after them, but the boys entered a rice field and disappeared. Not knowing their names, the actors called them "Heng" and "Ha", from the training method the boys taught them.

The method is as follows. A singer stands at a Goat Stance some distance from a wall. He places his two hands gently on his abdominal dan tian. He sings a long "heng" to the wall, and lets the echo bounce back. Then he sings a long "ha" to the wall and lets the echo bounce back. He repeats this process many times. Singing constitutes a crucial part in Cantonese opera, and this method is very effective.

Question 7

In your book "The Art of Shaolin Kung Fu" you briefly mentioned Shaolin qin-na and its use alongside the art of Tiger Claw. Could you please expand upon the art of qin-na to illustrate its application in modern combat and what exactly the art involves?

— Edward, England

Answer

Qin-na is unique in Chinese martial arts. As far as I know, no other martial arts have qin-na as a complete genre by itself.

Attacks can be in countless forms, but for convenience of study and practice, Chinese masters have classified all attacks into four categories or genres, namely

- striking — with the fist, palm, finger, elbow, shoulder, head.

- kicking — with the foot, toe, heel, shin, knee, hip.

- felling — using throwing, tripping, flicking, hooking, springing, pushing, pressing, etc.

- qin-na — consisting of two parts, qin and na.

There is no equivalent term for qin-na. I sometimes use “hold and lock” or “hold and grip” as a poor convenient term to stand for qin-na, but qin-na is actually much more than hold and grip, or hold and lock.

The crucial difference is that when you apply a hold, a grip or a lock on an opponent — unless you maim or kill him, like breaking his neck or suffocating him with a neck lock — you can only control him temporarily. As soon as you release your hold, grip or lock, he is free again to fight you.

But when you successfully apply a qin-na technique, you can release him immediately yet putting him out of combat -- and without hurting him seriously. The hallmarks of qin-na, therefore, are effectiveness and compassion. It is no surprise that Shaolin Kungfu is well known for qin-na, as effectiveness and compassion are also the hallmarks of Shaolin teaching.

The set of kungfu techniques known as "Shaolin Seven Two Techniques of Qin-Na" is famous in kungfu circles. There are now different versions of this set. Please see January (2000) Part 3.

“Qin” means catch, hold or lock, and it is not much different from the holds and locks in other martial arts except that in qin-na it appears to be simpler. It is therefore in "na" that qin-na is unique. “Na” literally means “take”, but here it refers to gripping in a very special way that puts an opponent out of action without permanently harming him.

To apply qin-na, an exponent first has to “qin”, i.e. immobilize the opponent for a split second. Then he applies the “na”, i.e. put the opponent out of action with a special grip. Usually the exponent uses one hand to “qin”, and the other hand to “na”, but sometimes he may use the same hand both to “qin” and “na”.

Here are some simple examples. An opponent throws a right thrust punch at me. I grasp his right wrist with my right tiger-claw, instantly bend his right arm slightly, and apply my left tiger-claw at some vital points at his right elbow.

Then I can release his right arm, but he would not be able to fight effectively with me again as he would be unable to use his right hand. By gripping at his vital points with some internal force, I have stopped the energy flow to his right arm. However the injury is temporary; he can seek a master or an acupuncturist to restore the energy flow to his arm.

If the situation is favourable, after grasping his right wrist with my right tiger-claw, I may use the same tiger-claw to grip the vital points at his right wrist, thus interrupting the energy flow to his right arm.

As the energy flow of the arm flows from the shoulder through the elbow to the hand, can I stop the flow by gripping at his wrist, which is at the lower end of the flow? Yes I can — if I know how and have the internal force. Energy flow along the arm is not just one way; it flows down from the shoulder to the hand in three main meridians, and up again from the hand to the shoulder in another three meridians.

Alternatively, instead of grasping and then gripping his right wrist with my right tiger-claw, I can grasp and then grip his right elbow with my left tiger-claw. By gripping the appropriate vital points, I not only can stop his energy flow along the arm, but also may damage internal organs like the heart and the lungs. Nevertheless, the injury, including damage to internal organs, is temporary and can be rectified later.

Unlike in striking and kicking, and to some extent in felling, where force is usually more crucial than techniques in winning a combat, in qin-na both force and techniques are equally important. If you are overwhelmingly powerful, it does not matter much what techniques you use to strike or kick your opponent — you can knock him out with one blow.

In qin-na, you need good techniques to grasp your opponent, and manoeuvre him in such a way that not only he cannot escape but also he cannot counter strike you while you apply your “na” on him. But just having good techniques is not enough. You must have sufficient force to make your “na” effective.

There are three major approaches in employing “na” techniques to temporarily disable an opponent. They are:

- feng jing, which literally means “separating muscles”,

- chor jie, which is “disabling joints”,

- na xue, which is “gripping vital points”.

There are various arts to train internal force needed for applying “na” techniques, but the three most well-known are Tiger-Claw, Eagle-Claw and Dragon-Claw.

Question 8

After 8 lessons the instructor tested my qi in my dan-tian by hitting it with a 16 mm diameter wooden stick. The stick broke into two but I did not feel any pain at that time.

However, on the second day onwards I felt slight pain to the left of my dan-tian and then it became very painful or rather spasm aching which moved round my body and made breathing very uncomfortable from the fourth or fifth day onwards. I went for X-ray but the Western doctor could not find anything wrong!

The spasm aching moves around to the chest/abdomen/ribs/back, groin area, sometime it goes to the thighs and I also feel uncomfortable in breathing. Also sometime even my head feels like it is going to burst, i.e. like blood rushing upto my head! This makes me really worry as it may cause stroke.

— Yap, Singapore

Answer

I am attending to your questions first instead of putting them in the normal queue because yours seem to be an urgent problem.

Different teachers have different ways of teaching, but in our system we normally do not strike a student's dan tian as a test after only 8 lessons. Striking a dan tian (energy field) is generally more serious than striking a vital point, and may cause energy stored in it to run wide. Yours appear to be a case. Pain and breathing difficulty are two tell-tale signs of internal injury affecting your energy network.

Western doctors are unable to find anything wrong because “energy injury” is still not in their medical vocabulary. Unlike in traditional Chinese medicine which views a person from all his three dimensions of spirit, energy and form, Western medicine treats only the physical body. There is nothing wrong with your physical muscles and organs; the injury concerns energy flow, and may have serious consequences.

Lifting the Sky

I have stopped continuing to the Intermediate Level which is a 6-month course. Although the master asked me to continue because according to him it would be difficult to pick up again next time if I rested, somehow my instinct tells me to rest a few months first until I recover fully and not to follow his advice. I feel the master seems not be bothered with my health.

It would be extremely unwise if you continued to the intermediate course. Any teacher who does not understand the possible side-effects his internal art may bring, and does not know how to deal with them, must not teach that internal art.

You should not only rest, but seek treatment immediately, preferably from a genuine qigong or kungfu master who knows qigong therapy or kungfu medicine. If this is not possible, seek a good traditional Chinese physician. Politely confirm with him whether yours is a case of internal injury due to qi running wildly, and whether his herbal or any other treatment includes “tiao qi” or restoring normal energy flow.

Meanwhile you can do the following remedial exercise. Perform “Lifting the Sky” about 30 times. Check my book for details on how to perform the exercise correctly. Breathe in gently through your nose, but breathe out loudly (but not forcedly) with a “ho” sound through your mouth.

You may feel pain while performing this remedial exercise; do not worry about it. But if the pain is sharp and severe, you should stop the exercise immediately, rest for a while and resume the exercise when the pain has subsided. If the pain comes from your heart, instead of “Lifting the Sky”, do the following. Stand upright and relax. Breathe out loudly (but not forcedly) and slowly with a “ho” sound about 30 times. Do not worry about breathing in.

After breathing out, air will flow in naturally. After about 30 times of “Lifting the Sky”, or just breathing out, stand upright and relax, with your arms hanging effortlessly on both sides. Close your eyes gently, and open your mouth gently like smiling. Gently, very gently think of your dan tian. Remain at this standing position gently thinking of your dan tian, for about 5 minutes. Then rub your palms, warm and open your eyes, and walk about leisurely for 2 or 3 minutes to complete the exercise.

Practise this remedial exercise three times a day — any time before 9 in the morning, about 5 or 6 in the evening, and after 9 at night. It is important NOT to perform this exercise between 11 in the morning and 2 in the afternoon. Perform the exercise in a cool, airy place, preferably in the open with trees. This exercise can be practised in conjunction with any medical treatment you may be undergoing. Continue with the exercise until you are fully recovered.

The instructor said it was the runaway qi that could not go back to the original point at the dan-tian and not due to internal injury. He told me to focus on the acupoint on the sole of my feet and imagine the qi in the parts that felt pain to drain out to the ground. I feel only slightly better and could not cure this pain completely as the spasm pain or ache still moves about in my body.

I consulted a Chinese physician. He checked my finger nails one by one and told me that it was internal injury. I took his medicine which his subordinate told me was for relaxing my mind so that my injury could heal faster. He also said it was impossible to massage my body as my whole body was affected. I took his medicine for 2 weeks but it did not seem to help.

At the moment I took some Chinese rheumatic pills I bought from a Chinese sinseh shop and they help to reduce my pain by 70% now. It is quite effective. In Chinese medicine, they call it “wind” and it is believed that the “wind” can also run around in our body. Is “qi” and “wind” the same thing?

Yes, yours is due to runaway qi. Injury to qi falls under the category of internal injury.

Focusing on the vital points on the soles of your feet, i.e. the yong-chuan vital points, can only relieve the pain temporarily, but may not effect acomplete cure. You need to cleanse away the injured qi, restore harmonious qi flow and replenish good qi at the dan tian. This is treating your problem at its root cause.

“Wind” in Chinese medical jargon refers to uncontrollable qi moving about in the body causing pain and other troubles. Taking Chinese rheumatic pills can remove the “wind” but may not be sufficient to remove the internal injury sustained.

You can follow up the Chinese rheumatic pills by taking “tiet-ta chet lei san” (in Cantonese pronounciation), meaning “Fall-Hit Seven-Minigramme Power”, which is useful for overcoming your internal injury. Please note that it should be “tiet-ta chet lei san” and not just “chet lei san” which is another type of medicine for cleansing body-impurities in children.

You should proceed with the course of “tiet-ta chet lei san” after the course of rheumatic pills, and not taking the two at the same period. “Tiet-ta chet lei san” is very powerful; do not over eat. You can get it in most Chinese medical halls (shops) and the shopkeeper should be able to advise you about the correct dosage.

Or you can take some good “tiet-ta yun” (kungfu medicated pills). There are different types of “tiet-ta yun”. Get the type that specially deals with restoring harmonious qi flow rather than cleansing blood blockage. You must get the good ones; the money you pay for them is worth it.

What is going on and what is the best way to remove this excess qi from my body, or how to re-direct the qi back to my dan-tian and prevent it from running wild without control all over my body?

It has been one month already and I still feel pain in chest/abdomen/back, groin area; sometimes it goes to the thighs and I also feel uncomfortable in breathing. I heard it could even cause a person not able to walk or move around. Is that true?

Your energy network has been distorted. Pain results as qi cannot flow harmoniously. This affects the normal working of your body systems which may have far-reaching consequences, such as organic mal-function and humonal imbalance. But it is unlikely that you could not walk or move about.

Restoring to normal condition can be affected in many ways, such as through qigong therapy, herbal medicine, acupuncture and massage therapy, but it has to be done by a professional person.

Question 9

Answer

Question 10

Answer

Question 11

Answer

LINKS

Courses and Classes