GENERAL PRACTICE AND TRAINING, AND SPARRING METHODOLOGY

Sifu Zhang Wuji

Instructor, Shaolin Wahnam Singapore

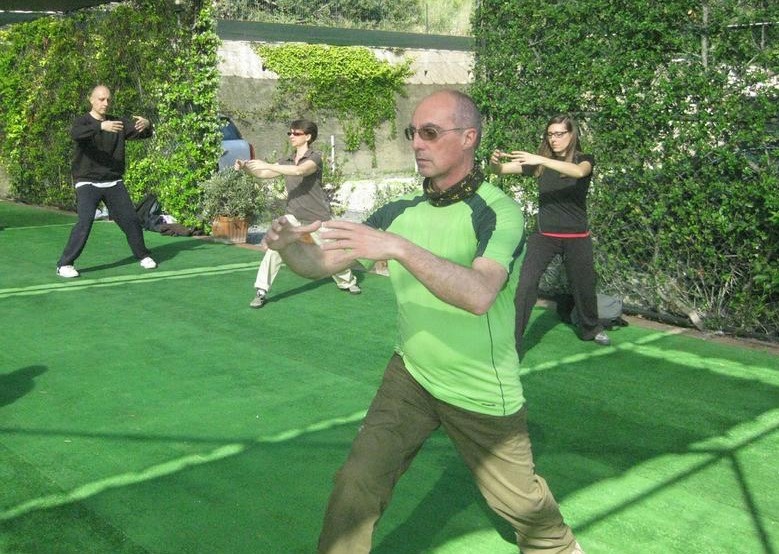

Zhan zhuang or stance training is very important in kungfu training

General View

I think there are several differences between Shaolinquan and Taijiquan, some identifiable by even a casual onlooker and for the purposes of this comparison, would like to group them into the following:

- General practice and training

- Sparring methodology

- Combat philosophy

- Training and use of internal force

I have heard it said often and I fully agree that many people are drawn to Taijiquan because of the “New Age” mystique of the art. Others want to learn a self-defence art but do not want to be associated with the aggression and brutal nature of karate or Muay Thai. They seek what they think is a gentle (and gentlemanly) art, devoid of the senseless violence of other marital arts, in other words, a sanitized art.

Another reason is that some teachers harp on the fact that Taijiquan is an “internal” art and does not rely on external exhausting training for power. Students are therefore attracted to the idea that they can achieve superhuman skills and powers without torturing themselves in training. I find it very quaint that this point of view is diametrically opposite to some of the modern Shaolin practitioners who believe in the “no pain, no gain, blood sweat and tears” regime.

Yet, even I began my Taijiquan, I had heard horror stories about the hellish training Yang Banhou and Yang Shaohou had to go through, driving them to suicide and running from home. It was then that I realized that Taijiquan is not an all-soft-like-tofu art. Like Shaolinquan (traditional), it can be very hard work indeed.

I got my first experience of this when I was put into the White Crane Flaps Wings posture for 5 minutes and not allowed to move. At the same time, despite the great fatigue in my arms and legs, we were told to relax into our posture. In all honesty, the instructor did not tell us how to relax and I was only able to do this after I had practiced Shaolin Cosmos qigong for a few months, and this is something for which I am truly grateful to Sifu.

Muscular Tension

In the early stages of Taijiquan training, there is no muscular tension at all during practice. This is to promote energy flow. Any tension would cause the muscles to constrict and block the flow of qi in each movement.

Sifu, you explained the difference between how a Wing Chun practitioner and a Taijiquan practitioner would train for internal force in your Q&A. Sifu noted that a Taijiquan practitioner watching a Wing Chun training his internal force would exclaim: “That is not qi, although we may call it jing4” because the Wing Chun expert would be tensing his arm.

I think the key difference here between Shaolinquan and Taijiquan is that at the beginning, Taijiquan is all soft and later proceeds to hard, whereas Shaolinquan has a mixture of both elements at the very outset. And my comments about Shaolinquan in this instance are tied to how I was taught by you, Sifu. Most other Shaolin schools would probably have a hard-only element.

Speed of Form Practice

In tandem with the absence of tension is the practice of the form at slow speed. Having had the golden opportunity to observe the Shaolinquan training during the Special Review course, I can see that the Shaolinquan students are fast but relaxed. They do not grimace and have frenzied expressions when sparring. They, however, practiced at a normal speed without artificially slowing down their movements (unless waiting for their partners to catch up).

In Taijiquan, the student speeds up his practice only when he can mobilize his qi to move fast, as directed by his mind, but not before. Unfortunately, because of the way Taijiuqan is taught today, an average student may never be able to direct his qi, so his form remains forever slow.

Stances

In terms of stance practice, Taijiquan stances are generally higher and smaller than the typical Shaolin Horse-Riding Stance and Bow-Arrow Stance, although all other stances are similar.

From what I understand, for zhan zhuang to be effective in building internal force, the body and legs must be lowered to a certain level. If it is too high, the qi movements will not be activated, and the stance is just another comfortable standing position. If it is too low, it is easy for the student to be too pre-occupied with the pain and effort and he will tense easily.

I have read that the Three-Circle Stance is the perfect median or compromise in this regard. But even among Taijiquan styles, there are many variations of this stance — some with the legs only shoulder-width apart, others up to two shoulders apart.

As Darryl put it in the forum, his students performing the demanding Horse-Riding Stance are more at ease than a Taijiquan dancer doing the easier Three-Circle Stance.

In Shaolin Wahnam, both Taijiquan and Shaolinquan are performed with qi flow, without muscular tension, even in sparring. Here Sifu Tim Franklin of England spars with Marko Ham of Finland, and their movements are fast and relaxed, yet powerful

Sparring Methodology

I am personally most familiar with the Shaolin Wahnam methodology after Sifu had generously provided its details on the website. I have done some research on classical Taijiquan sparring training to compare methodologies.

The traditional Taijiquan sparring methodology seems to be quite similar to that of Shaolin Wahnam except for some differences I will highlight below.

There is the practice of individual patterns, but according to some sources, the patterns are not always practiced with explicit combat applications in mind. The reason is that unlike Shaolinquan where there is a technique for virtually every situation, the limited repertoire of Taijiquan means the techniques are not restricted to a few or even several applications. Instead, the way is to let the mind-body express the technique naturally in countless variations. [1] It is not possible to practice countless variations so there is no rigid practice of any particular application.

Zhang Wuji

Sifu's Comments

This view of practicing patterns without explicit combat applications in mind may hold true for some teachers but untrue for others. Or for the same teachers, it may be true in some situations and untrue in other situations.

In Shaolin Wahnam, both in Shaolinquan and Taijiquan, we do not normally practice patterns with their explicit combat applications in mind. At the beginners' stage we focus on correctness of form. But when a particular way of movement or form is needed, the combat application may be shown to the students.

Most schools today practice Shaolinquan and Taijqian without the combat applications in mind, simply because most instructors today do not know them. Among the few schools that know combat applications, their students also normally practice the patterns without thinking of their specific applications in both Shaolinquan and Taijiquan.

In Shaolin Wahnam, in both Shaolinquan and Taijiquan the combat applications are introduced in one-step sparring after students have familiarized themselves with the form.

Wong Kiew Kit

The idea is that the techniques in the form are practiced so often they become natural and part of the subconscious mind. If they are practiced in a set manner with a partner, the exponent may be conditioned to think this is the only way the technique is used, instead of flowing with the enemy and adapting the technique specifically to what the enemy is doing, ie, a spontaneous modification for that combat situation. One author described this as practicing the principle of the posture rather than the applications.

Zhang Wuji

Our approach in Shaolin Wahnam is quite different. At the beginners' stage, students are conditioned to response to specific attacks in specific ways spontaneously. For example, when an opponent throws a punch, we spontaneously respond with “Single Tiger Emerges from Cave”; when he kicks, we spontaneously respond with “Lohan Strikes Drum”.

But even at this early stage of training, our students learn to choose the best counters. If the punch is high, for example, we would use “Golden Dragon Plays with Water” instead of the “Single Tiger”; if the punch is low, we would use “False Leg Hand Sweep”. And when we would normally use the “Single Tiger”, we learn to choose using a left mode or a right mode, and sometimes we may substitute another pattern like “Bar the Big Boss”.

In short, we are trained not just to respond spontaneously in sparring, but to do so wisely and effectively, and sometimes with options for alternatives. All these are practiced at the beginners' level. At advanced levels, our students not only can use a greater variety of skills and techniques spontaneously and effectively, but also employ tactics and strategies. The video clips showing the sparring sessions between Anthony and Anton, between Eugene and David, and between Emiko and Michael illustrate some of these sparring methodologies.

Wong Kiew Kit

I thought it may be helpful to reproduce what Sifu Stier said on the forum:

"It is well known that good Tai-Chi can easily be used as a 'moving meditation', so all that is needed then is to practice in a meditative state of mind for enough time at each practice session to allow the Forms to be programmed into the deeper mind."

But this view may not be universally true. I have come across books written by acknowledged masters such as Chen Yanlin and Wang Peisheng, which describe the repeated practice of certain postures as combat training.

Zhang Wuji

We are grateful to Sifu Stier for his valuable contributions to our discussion forum. But here if Sifu Stier means that by practicing forms in a meditative mind long enough, one would be combat efficient, I would disagree.

If Sifu Stier's view were true, then there would be many people able to use Taijiquan and other styles of kungfu for combat. The sad fact is that of the millions of people who have practiced Taijiquan and other kungfu forms in meditative mind for years, only a pitiful minute minority can effectively use their forms for combat.

I also disagree with Chen Yanlin and Wang Pensheng if they mean that repeatedly practicing forms while thinking of their combat applications, but without actually practicing the combat applications, one can be combat efficient.

No matter for how long one may practice kungfu forms, regardless of whether he has the combat applications in meditative mind or not, he cannot effectively use the forms for combat unless he has practiced combat application sufficiently and methodologically.

The evidence is everywhere. Thousands of practitioners can demonstrate forms beautifully, as a result of their dedicated form practice, but very few can use them for combat. Modern wushu and Taijiquan practitioners are good examples. Many of them realize that methodological combat training is necessary, but they simply do not have the sparring methodology.

The evidence is also present in other martial systems, though it is not so obvious. Many Karate and Taekwondo practitioners, for example, have practiced their forms dedicatedly for years usually with understanding of their combat applications, yet they cannot use them effectively for combat! If they could, they would not punch and kick one another wildly in their sparring; they would not accept being routinely hurt as part of their training.

Wong Kiew Kit

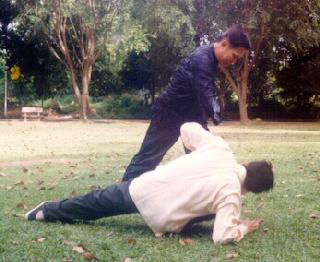

Combat Sequences are used in Wahnam Taijiquan to train combat efficiency. Here Grandmaster Wong used his shoulder to throw Sifu Goh Kok Hin to the ground.

Also, combat sequences seem to be absent from traditional Taijiquan training, probably because Pushing and Striking Hands were meant to be that bridge between form practice and free sparring. Sparring sets were however used as part of combat training. They were first used to develop combat skills, and later the sparring sets were done out of sequence much like the variations in the Shaolin Wahnam combat sequences.

Sifu's Comments

Combat sequences are found in traditional Taijiquan training, but may not be practiced in the same ways as we do in Shaolin Wahnam.

The basic unit of Taijiquan (and other kungfu styles) is a pattern. A series of patterns linked together in some meaningful way form a sequence. A series of sequences form a set.

Let us take the 24-Pattern Taijiquan Set. In the beginning you may perform all the patterns, which actually number more than 24, one at a time. As you progress you are likely to link some patterns together in your performance. For example, you may perform the three patterns of “Green Dragon Shoots Pearl” together as if they were one long pattern. In this case, the three “Green Dragons” form a sequence.

Or you may not stop after the third “Green Dragon”. You may continue with “Playing the Lute” and the four patterns of “Repulse Monkey”. In this case the eight patterns from the first “Green Dragon” performed continuously to the fourth “Repulse Monkey” forms a sequence.

The same principle applies in a sparring set. Let us say in a sparring set, each of the two sparring partners makes 36 patterns. They do not perform the 36 patterns one at a time. They perform the 36 patterns in sequences, though the link between one sequence and another is so often smooth that many practitioners may not be aware of them. This unawareness is especially so when many practitioners perform a sparring set for demonstration, rather than training combat application as it is actually meant for.

Wong Kiew Kit

LINKS

- 1. The Evolution of Taijiquan from Shaolinquan

- 2. General Practice and Training, and Sparring Methodology

- 3. Combat Philosophy on Retreat and Yielding

- 4. Difference in Stances

- 5. The Use of Internal Force

- 6. Fa-jing and Qin-na

- 7. Academic Questions and Direct Experience

- 8. Yin-Yang, God and Health

- 9. Spirituality and Over-Training

- 10. Questions on Sinew Metamorphosis

- 11. Questions on Breathing Methods and Control

- 12. Taoist Philosophy and Concept of Open and Close